Synchronization Engine

The synchronization engine provides the ability to keep records in multiple systems in sync. An example of this is synchronizing task and schedule items in NexJ CRM with Microsoft Exchange. We will use this as an example for explaining synchronization engine concepts.

Purpose

NexJ's applications are based an object model, usually mapped to an underlying database. Some of the data represented in the object model is generated by users interacting with the application directly. In a standard deployment, however, much if not most of the data will originate in other systems on a company's network. NexJ needs to be able to read information from these systems, to register and react to events signaled by these systems, to notify these systems of events in NexJ's application and to write data to these systems.

All of this communication is done by means of Messages. The integration framework is essentially a library of tools for defining how messages are to be created, manipulated, sent and received by an application. Most of this functionality is accessible through specialized UI in the Studio.

Messages

The format and structure of the messages used depends on the external system with which we are communicating. Within application code, we can generally ignore the format: messages are represented as Transfer Objects. Only at the point of sending or receiving a message do we need to convert to or from the appropriate format.

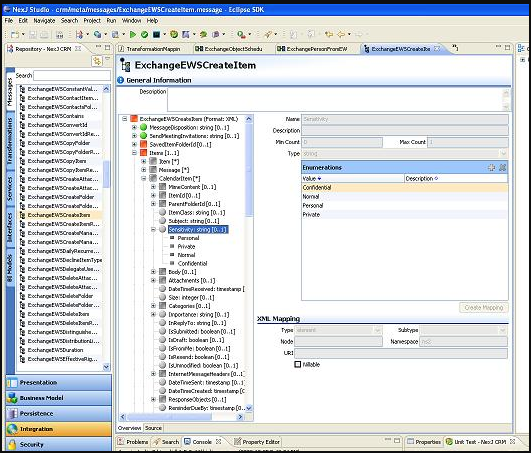

The message type editor looks like this:

One message format is of particular interest. The Object message format is a representation of an object instance. Generally, an object message type is associated with a class, and contains a subset of the attributes of the class. A transfer object that is formatted as an object message type directly manipulates our object model: if an object with the same key as the message already exists, then that object is loaded and modified to match the message; if an object does not already exist, then one is created. Similarly, the framework provides a mechanism for automatically generating object messages from object instances.

The object message format is the foundation of our approach to synchronizing data with external systems. Object instances are parsed into transfer objects, manipulated and sent to external systems in a format that those systems can process. Messages from external systems are received, manipulated, converted into object messages, then directly merged into the object model. The details are usually not that simple, but sometimes you get lucky.

Channels

Ultimately, messages must be sent or received to be of any value. At design time, it is not known exactly where the messages will be going or coming from, though we do have some idea what format they will have and what transport (HTTP, UDP, etc.) will be used. Channels are abstract message source/destinations: their transport is known, but their connection parameters are not. Services can be configured to send messages and receive responses on channels. Service bindings can be used to specify that messages received asynchronously by a channel are to be processed by specific integration services.

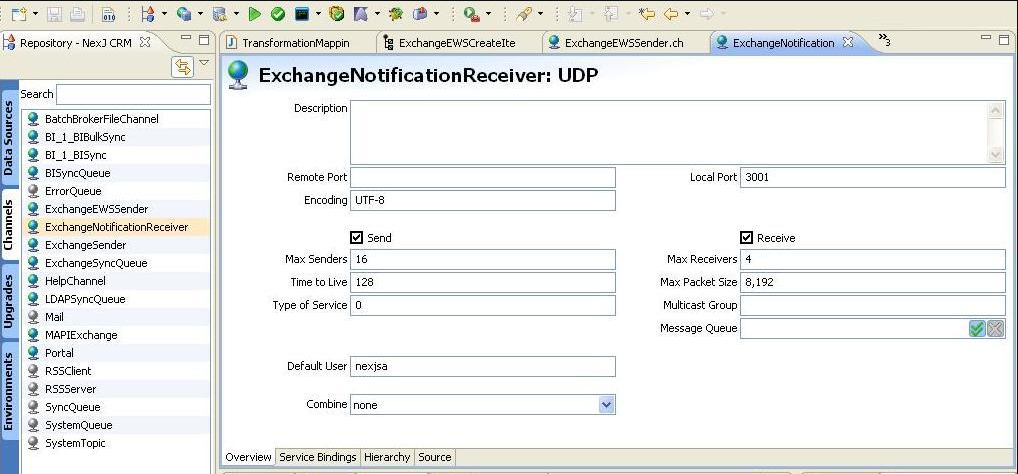

Here is the channel editor:

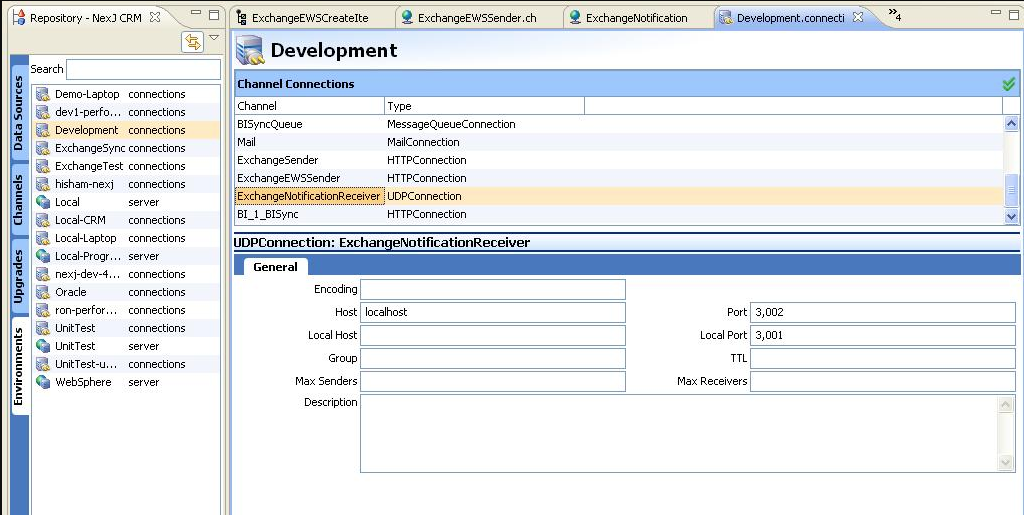

When the application is deployed, the connection parameters for all channels must be specified:

Transformations

Transformations transform an instance of one message type to another message type. In a normal synchronization scenario, two message types will be used: one object message type very closely matching a class; and one message type with a structure and format understood by the external system. The application must be able to translate from one format to another and back.

Services

Deciding which messages to process, which to ignore, where to send them, how to transform them, and the like, is managed through specialized workflows called Services. Each service has a state (stored in a variable called this). The state is a working copy of the message as it is transformed, parsed, formatted, etc.

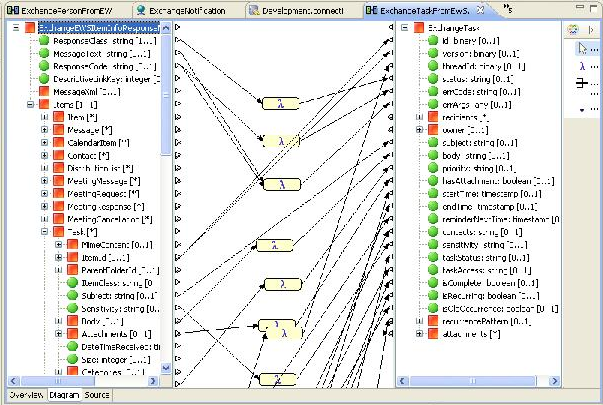

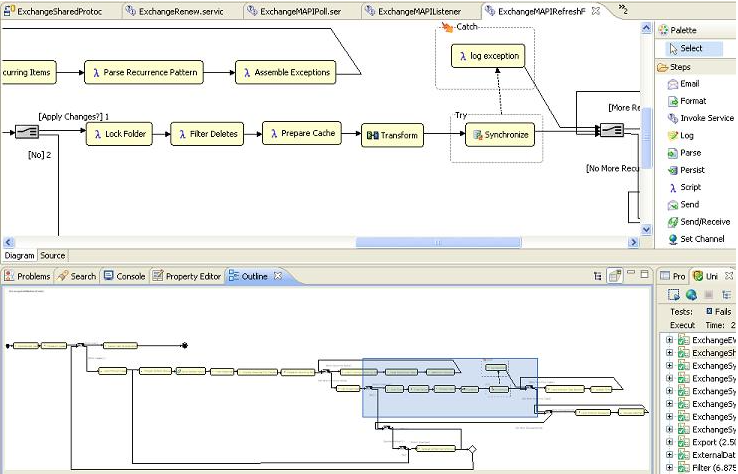

Here's a portion of one of the exchange sync services:

Synchronization Classes

Synchronization Engine

The dirty work takes place at the point where we either format an object message (and merge it into our object model) or decide that an object message must be dispatched on a service for consumption by an external system.

There are two situations of interest. In the first case, we have received a message from an external system and converted it into an object message. We now wish the message to be formatted into an object and merged with our data model. This is usually done with a synchronize step in a service. For each message entering a synchronization step, we try to find a previous instance of the corresponding object. If one is found, then we check to see if there have been any changes to the object since the last time the external system received a copy of it (or gave us a copy). If there have been changes, then we determine on which attributes there are conflicts. Once the object has been found (or created) and any conflicts have been located, all this information is passed to the script of the synchronize step. The script allows an application to "veto" changes proposed by the synchronization engine, and to make decisions about how to resolve any conflicts.

In the second case, a change has been made to data in our object model. During commit of this change, the framework detects that an instance of a class marked for synchronization is being committed, finds interested external systems, builds an object message, and dispatches it to the services configured for all interested external systems.

Both of these scenarios imply that we have some "meta" knowledge about business objects in our model, and their relation to external systems. Today, I will (very briefly) outline the nature of this knowledge.

SysSyncTarget

Every external system with which we synchronize is modeled as a synchronization target. A synchronization target specifies the service to which to send outbound messages, and a bunch of configuration parameters. In the Exchange synchronization code, we have a subclass of SysSyncTarget on which we put additional information, such as the channels on which to send and receive Exchange messages.

SysSyncClass

We relate business logic classes to targets through subclasses of SysSyncClass. For each class we want synchronized with external systems, and for each external system interested in that class, we create one instance of SysSyncClass. SysSyncClass is an interface with a bunch of hooks for customizing the behaviour of the synchronization framework when dealing with instances of the corresponding business class.

SysSyncLink and SysSyncLinkClass

Data storage systems are usually compartmentalized in some way. You don't just dump records in one bin, but rather into many different files, folders, tables, etc. A SysSyncLink represents one of these abstract compartments in a SysSyncTarget. This class is usually subclassed to provide storage for attributes specific to the external system involved.

Every link of a target may not be interested in every class. A SysSyncLinkClass instance serves to associate one or more SysSyncClass instances with a link. Many links will likely share the same instance(s) of SysSyncClass, but most links will have very few associated classes (often only one.)

SysSyncObject and SysSyncGroup

In order to determine whether an external system has seen a copy of any particular instance in our object model requires us to track information about the most recent version of each object sent to or received from each external link. This information is tracked in SysSyncObject instances. Usually there is one sync object per synchronized instance, per link to which it is synchronized.

In some cases one NexJ instance will be synchronized with multiple instances on an external system. The prime example of this is a meeting: we have one copy of the meeting, but Microsoft Exchange stores one copy of the meeting in the mailbox of each participant. In this case, we need to keep track of the group of sync objects corresponding to our one NexJ instance. This is done with an instance of SysSyncGroup.

Unlike the other classes mentioned above, SysSyncObject and SysSyncGroup are not generally subclassed by an application.